Are SAFEs Dangerous?

SAFEs can be a powerful fundraising tool—but they also carry real risks to existing equity holders. For founders, the danger lies not in the document itself, but in misunderstanding its terms and consequences. Read on to learn why.

SAFEs v. Convertible Notes

Risk Comparison Between SAFEs and Convertible Notes (Low Risk)

SAFEs and convertible notes each carry their own advantages and disadvantages. From a founder’s perspective, convertible notes are generally riskier in the early stages due to their repayment obligation at the maturity date and interest accrual. A SAFE carries none of these features—if the company never raises a priced equity financing round, there is no obligation to repay the investment until a liquidity event.

That said, when a priced equity financing occurs, the risk dynamic can shift. Convertible notes typically convert on a pre-money basis, meaning they dilute each other and generally result in less dilution to the founders than SAFEs with post-money valuation caps—which fix the investor’s ownership percentage and push onto the founder all dilution from the securities converting into the financing. (See more on dilution risk below.)

For a deeper dive on the differences between SAFEs and Convertible Notes read: Convertible Notes vs. SAFEs: Choosing the Right Pre-Seed Financing Tool.

SAFE Conversion and Founder Dilution Risk (High Risk)

SAFEs convert into equity upon the occurrence of a triggering event, most commonly a priced equity financing, such as a Series Seed or Series A round. At that point, the SAFE converts into shares of preferred stock, with the number of shares determined by either a valuation cap, a discount rate, or the more favorable of the two.

That is why we encourage founders to push for discount-only SAFEs where possible—even if investors initially resist. For investors, the longer a SAFE is outstanding, the riskier accepting a discount-only SAFE is.

Overlapping SAFEs with Different Investor-Friendly Terms

There are three primary types of SAFEs: those with a valuation cap, a discount or an MFN (most favored nation) clause. While these features are designed to reward early investors for taking on risk, they can present significant risks to founders if not used carefully, particularly when they are combined with one another.

The MFN clause poses the greatest risk to founders when combined with either a discount rate or valuation cap SAFE—MFN clauses allow an investor to “upgrade” their SAFE terms if the company later issues SAFEs with more favorable economics. If multiple SAFEs include MFN clauses, it becomes difficult—if not impossible—for founders to predict final conversion terms, creating a moving target for the cap table and introducing hidden, compounding dilution. MFN clauses are neutralized when successive SAFEs are raised with equal to higher caps over time or the same or lower discounts.

MFN clauses also make capitalization tables more challenging to calculate because founders will not know if the SAFE holder has “upgraded” their terms. As a result, without careful planning and constraint, a company can unintentionally give away significant equity before its first priced round—even if each individual SAFE seems reasonable on its own.

Risk of Investor-Friendly Side Letters (Medium Risk)

Side letters can pose serious risks for founders and should be used only after careful consideration of the potential consequences and understanding the terms included. These agreements often accompany SAFEs and grant investors additional rights that go beyond the standard SAFE terms. The most common provisions include:

How Founders Can Protect Themselves From These Risks

While SAFEs carry meaningful risks, they remain a valuable and widely used fundraising tool—especially for early-stage startups. The key for founders is to understand those risks and proactively manage them. Founders can better protect themselves by:

Conclusion

So, are SAFEs dangerous? Not inherently—but they can be if founders do not fully understand their terms and the long-term consequences. Without careful planning, SAFEs can lead to unexpected dilution, reduced flexibility, and complex, investor-heavy cap tables—particularly when post-money caps and side letters are stacked across multiple rounds.

When used thoughtfully—with attention to structure, investor rights and cumulative dilution—SAFEs remain a founder-friendly tool for raising early-stage capital efficiently. The key is to treat every SAFE issuance like an equity deal: Negotiate terms carefully, forecast dilution realistically and always consider the impact on future rounds.

SAFEs v. Convertible Notes

What is a Simple Agreement for Future Equity (SAFE)?

SAFEs are an investment contract under which investors provide capital to a startup in exchange for the right to convert their investment into equity at a later date, typically at a discount or based on a valuation cap (pre-money or post-money). SAFEs were originally introduced by Y Combinator in 2013 as a founder-friendly alternative to convertible notes that would be less administratively burdensome to execute. Additionally, SAFEs are generally not considered debt instruments that have benefits and costs for the investors. Instead, SAFEs represent a contractual right to purchase equity under specified conditions.

Usually, SAFEs convert into a shadow series of preferred stock—a subclass of preferred stock issued to SAFE holders upon conversion when their effective price per share is lower than the price paid by new investors in the same financing round with cash (typically due to a discount or valuation cap). While shadow preferred stock carries the same rights (e.g., dividends, voting and liquidation priority) as the standard preferred stock, their liquidation preference and other economic rights reflect the lower original purchase price paid by the SAFE holder because of their discount.

What is a Convertible Note?

A convertible note is a type of short-term debt that is designed to eventually convert into equity, typically due to a discount or valuation cap. Convertible notes are frequently used by startups that need capital and do not want to undergo the time and cost associated with a preferred stock financing but have investors who prefer to hold a debt security and earn interest. Similar to a SAFE, they are advantageous to a preferred stock financing because the startup does not need to provide a valuation at the time of the loan and the terms for negotiation are significantly less. Instead, this occurs later during an equity financing round when the notes convert, often into a shadow series of preferred stock.

Key Differences

The significant distinction between SAFEs and convertible notes is that SAFEs are generally considered equity rather than debt. This distinction will impact how the SAFEs are treated in a liquidation event (i.e., junior to debt, even with the preferred and ahead of the common) as well as how investors may treat their holding periods for tax purposes. SAFEs have no maturity date with a repayment obligation and do not accrue interest. Additionally, SAFEs are frequently issued with a side letter that gives the investor more favorable terms while keeping the form of the SAFE the same for all investors. Side letters are less frequently issued with convertible notes because the form of note is more highly negotiated to include required investor terms.

SAFEs are an investment contract under which investors provide capital to a startup in exchange for the right to convert their investment into equity at a later date, typically at a discount or based on a valuation cap (pre-money or post-money). SAFEs were originally introduced by Y Combinator in 2013 as a founder-friendly alternative to convertible notes that would be less administratively burdensome to execute. Additionally, SAFEs are generally not considered debt instruments that have benefits and costs for the investors. Instead, SAFEs represent a contractual right to purchase equity under specified conditions.

Usually, SAFEs convert into a shadow series of preferred stock—a subclass of preferred stock issued to SAFE holders upon conversion when their effective price per share is lower than the price paid by new investors in the same financing round with cash (typically due to a discount or valuation cap). While shadow preferred stock carries the same rights (e.g., dividends, voting and liquidation priority) as the standard preferred stock, their liquidation preference and other economic rights reflect the lower original purchase price paid by the SAFE holder because of their discount.

What is a Convertible Note?

A convertible note is a type of short-term debt that is designed to eventually convert into equity, typically due to a discount or valuation cap. Convertible notes are frequently used by startups that need capital and do not want to undergo the time and cost associated with a preferred stock financing but have investors who prefer to hold a debt security and earn interest. Similar to a SAFE, they are advantageous to a preferred stock financing because the startup does not need to provide a valuation at the time of the loan and the terms for negotiation are significantly less. Instead, this occurs later during an equity financing round when the notes convert, often into a shadow series of preferred stock.

Key Differences

The significant distinction between SAFEs and convertible notes is that SAFEs are generally considered equity rather than debt. This distinction will impact how the SAFEs are treated in a liquidation event (i.e., junior to debt, even with the preferred and ahead of the common) as well as how investors may treat their holding periods for tax purposes. SAFEs have no maturity date with a repayment obligation and do not accrue interest. Additionally, SAFEs are frequently issued with a side letter that gives the investor more favorable terms while keeping the form of the SAFE the same for all investors. Side letters are less frequently issued with convertible notes because the form of note is more highly negotiated to include required investor terms.

- Maturity Date. SAFEs convert only upon a triggering event. In contrast, convertible notes mature within 12–24 months, at which point investors may demand repayment unless the note is converted or extended (usually requiring investor consent). Founders benefit from this flexibility in SAFEs and sometimes choose to do successive SAFE financings because there is no risk of maturity/repayment.

- Interest. Convertible notes accrue moderate interest (typically 4–8%), which either converts into equity or must be paid in cash. SAFEs accrue no interest, reducing dilution and administrative burden. Convertible note interest rates are typically lower than what a Company of equivalent risk would be charged by a financial institution or private lender.

- Repayment Obligation. If no triggering event occurs, SAFE holders will continue to hold their SAFE, payable at an exit event, whereas convertible note holders can demand repayment at maturity. This difference makes SAFEs inherently more founder-friendly.

- Side Letters. SAFEs frequently include side letters granting investors additional rights—like pro rata rights, MFN clauses, cap resets, optional conversion, information rights or board observer seats. These extras can substantially increase investor leverage and founder dilution if not carefully managed (more on this below). These rights also put SAFEs on more equal footing to a convertible note from the investors’ perspective.

Risk Comparison Between SAFEs and Convertible Notes (Low Risk)

SAFEs and convertible notes each carry their own advantages and disadvantages. From a founder’s perspective, convertible notes are generally riskier in the early stages due to their repayment obligation at the maturity date and interest accrual. A SAFE carries none of these features—if the company never raises a priced equity financing round, there is no obligation to repay the investment until a liquidity event.

That said, when a priced equity financing occurs, the risk dynamic can shift. Convertible notes typically convert on a pre-money basis, meaning they dilute each other and generally result in less dilution to the founders than SAFEs with post-money valuation caps—which fix the investor’s ownership percentage and push onto the founder all dilution from the securities converting into the financing. (See more on dilution risk below.)

For a deeper dive on the differences between SAFEs and Convertible Notes read: Convertible Notes vs. SAFEs: Choosing the Right Pre-Seed Financing Tool.

SAFE Conversion and Founder Dilution Risk (High Risk)

SAFEs convert into equity upon the occurrence of a triggering event, most commonly a priced equity financing, such as a Series Seed or Series A round. At that point, the SAFE converts into shares of preferred stock, with the number of shares determined by either a valuation cap, a discount rate, or the more favorable of the two.

A. Pre-Money vs. Post-Money Valuation Caps

One of the most misunderstood but critical distinctions is whether the valuation cap is pre-money or post-money:

- A pre-money valuation cap calculates the SAFE investor’s ownership before new money and before the other SAFEs are converted, meaning all SAFEs dilute each other because the numerator in the conversion price calculation increases by the value of the convertible securities that are converting.

- A post-money valuation cap calculates the investor’s ownership after all other SAFEs are accounted for, giving each investor a fixed ownership percentage—and pushing all dilution onto the founder because the numerator in the conversion price calculation is fixed.

Founders often assume that raising $1 million on a $10 million valuation cap means they are giving up 10% of the company. That is true only if the cap is post-money—in which case the investor is guaranteed 10% ownership immediately before the next equity round. If the cap is pre-money, the actual dilution may be lower, depending on how many other SAFEs or convertible notes exist. At a maximum, assuming no other convertibles are outstanding, the investor holding a pre-money capped convertible security would expect to receive ownership equal to 9.09% ($1 million / $11 million).

Post-money caps are more predictable for investors but more dangerous for founders because they guarantee a fixed ownership percentage. That means that if a Company has issued a significant amount of SAFEs at a relatively low post-money cap, a significant portion of the pre-money cap table can shift to the SAFE holders, decreasing the founders’ stake dramatically.

B. Discount-Only SAFEs Can Be Better for Founders

Discount-only SAFEs are generally more favorable for founders, especially if the next preferred stock financing is priced at a higher valuation. Because the discount applies to the preferred stock price per share, it functions more like a pre-money instrument and often results in less dilution than a post-money valuation cap. If the priced round’s valuation is significantly higher than the conversion cap (i.e., a higher percentage than the discount), the discount-only SAFE is going to be much more favorable.

For example, a 20% discount is better than a $5M post-money cap in any preferred stock round priced above ~$6.25M, based on this quick formula:

For example, a 20% discount is better than a $5M post-money cap in any preferred stock round priced above ~$6.25M, based on this quick formula:

Approximate break-even point = Valuation Cap / (1 - Discount Rate) ? $5M / 0.8 = $6.25M

That is why we encourage founders to push for discount-only SAFEs where possible—even if investors initially resist. For investors, the longer a SAFE is outstanding, the riskier accepting a discount-only SAFE is.

C. Why “Stacking” Post-Money Cap SAFEs Can Be Dangerous—Compounding Dilution

Stacking multiple post-money SAFEs—especially with varying terms—can quietly erode a founder’s ownership long before a priced equity round occurs, making the Company’s future precarious (i.e., broken cap table). Because each post-money SAFE guarantees the investor a fixed percentage of the company immediately before the next equity financing, every new SAFE issued further shrinks the founder’s slice of the cap table in the pre-money. Founders often do not realize the extent of the dilution until all the SAFEs convert at once—compounding the impact and potentially pushing the founder below majority ownership before any institutional investor even joins the cap table.

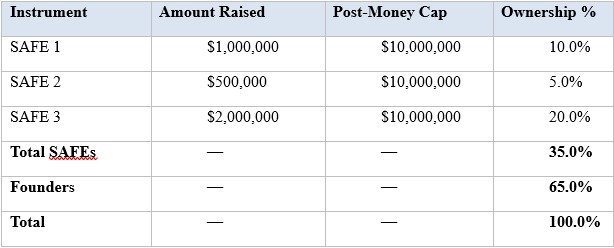

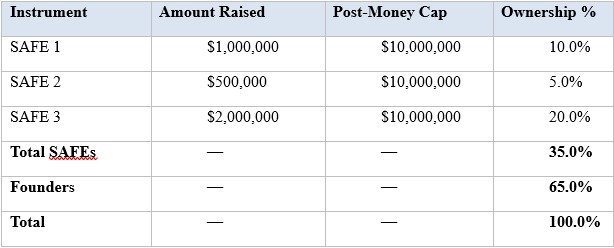

Consider this example: Suppose the company raises $5 million at a $20 million pre-money valuation, resulting in a $25 million post-money valuation. Prior to this Series A, the company has raised three SAFEs, each with a $10 million post-money valuation cap. Immediately before the Series A financing, the cap table would look like this:

Consider this example: Suppose the company raises $5 million at a $20 million pre-money valuation, resulting in a $25 million post-money valuation. Prior to this Series A, the company has raised three SAFEs, each with a $10 million post-money valuation cap. Immediately before the Series A financing, the cap table would look like this:

At this point, the SAFEs convert into their fixed post-money percentages (10%, 5%, 20%), and the founders own the remaining 65% of the company.

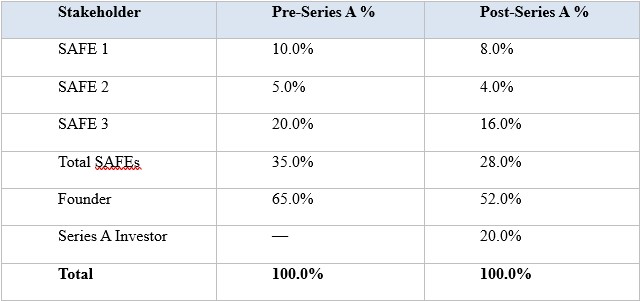

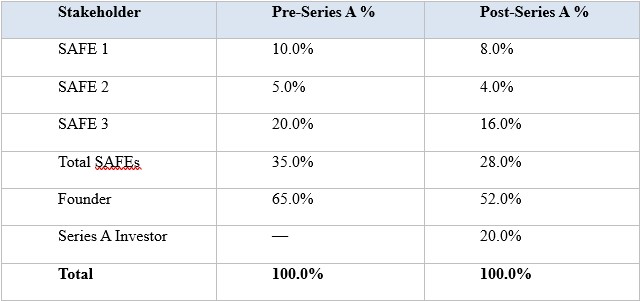

Next let us look at what the company’s cap table will look like immediately following the Series A financing:

Next let us look at what the company’s cap table will look like immediately following the Series A financing:

This example illustrates how stacking post-money SAFEs can quietly and significantly dilute founders—before a priced equity round takes place. What often looks like a quick, founder-friendly fundraising tool can, in aggregate, pre-allocate a large portion of the company to early investors, leaving the founder with a shrinking stake and less control. When the Series A financing arrives, the effect compounds further, particularly when founders are required to increase the option pool as part of the pre-money valuation—a standard ask that introduces yet another layer of dilution (on the founders and converting SAFE holders). Importantly, the ownership percentages shown above assume no such option pool expansion, meaning the real-world impact is often even more severe. Without careful planning and cap table modeling, founders can unintentionally cross below key ownership and control thresholds at a critical stage—making it essential to treat every SAFE issuance as a true equity decision with the conversion in mind, not just a short-term fundraising fix.

For a more in-depth review on cap table math, read: Understanding the Basics of Cap Table Math in Startups.

For a more in-depth review on cap table math, read: Understanding the Basics of Cap Table Math in Startups.

Overlapping SAFEs with Different Investor-Friendly Terms

There are three primary types of SAFEs: those with a valuation cap, a discount or an MFN (most favored nation) clause. While these features are designed to reward early investors for taking on risk, they can present significant risks to founders if not used carefully, particularly when they are combined with one another.

The MFN clause poses the greatest risk to founders when combined with either a discount rate or valuation cap SAFE—MFN clauses allow an investor to “upgrade” their SAFE terms if the company later issues SAFEs with more favorable economics. If multiple SAFEs include MFN clauses, it becomes difficult—if not impossible—for founders to predict final conversion terms, creating a moving target for the cap table and introducing hidden, compounding dilution. MFN clauses are neutralized when successive SAFEs are raised with equal to higher caps over time or the same or lower discounts.

MFN clauses also make capitalization tables more challenging to calculate because founders will not know if the SAFE holder has “upgraded” their terms. As a result, without careful planning and constraint, a company can unintentionally give away significant equity before its first priced round—even if each individual SAFE seems reasonable on its own.

Risk of Investor-Friendly Side Letters (Medium Risk)

Side letters can pose serious risks for founders and should be used only after careful consideration of the potential consequences and understanding the terms included. These agreements often accompany SAFEs and grant investors additional rights that go beyond the standard SAFE terms. The most common provisions include:

- Pro Rata Rights. These give SAFE holders the right to participate in future financing rounds to maintain their ownership percentage. While common in later-stage deals, including them early can lead to unexpected dilution and reduced flexibility when bringing in new investors.

Negotiation Tip: Force the pro rata rights to sunset at the future financing when the SAFEs convert. - Information Rights. These grant investors access to key company materials such as financial statements and updated capitalization tables. Although fairly standard at later stages, granting them too early can create administrative burdens and disclosure obligations for founders that do not have the resources to meet investor needs.

- Most Favored Nation (MFN) Clauses. MFN provisions allow investors to “upgrade” their SAFE to match better economic terms offered in later SAFEs. As described above, this can lead to unpredictable dilution and make cap table modeling more difficult.

- Board Observer Rights. These give the investor the right to attend board meetings and access sensitive board materials, but not to vote. Still, this can be risky for founders, as observers may influence board dynamics, slow decision-making, or leak confidential information. It is difficult to dis-invite a board observer once these rights are granted.

- Major Investor Rights. These provisions carve out a special class of investor—typically based on the size of investment—and grant them enhanced rights once their SAFE converts into equity. Such rights often include expanded information rights, pro rata rights, and in some cases, approval or veto rights over key corporate actions. A concerning trend is that investors are increasingly pushing for indefinite Major Investor status, meaning these enhanced rights do not terminate after the next equity financing, but instead continue indefinitely pursuant to the Investors’ Rights Agreement adopted at the preferred stock financing. This shift can lead to long-term governance complications, reduce founder flexibility, and make future financings more difficult—especially when multiple early investors qualify as “Major Investors.”

Negotiation Tip: Require that Major Investor status terminate after the next priced equity round unless the investor meets future thresholds. Do not allow indefinite board observer rights or information access unless they are truly justified by check size or strategic value.

How Founders Can Protect Themselves From These Risks

While SAFEs carry meaningful risks, they remain a valuable and widely used fundraising tool—especially for early-stage startups. The key for founders is to understand those risks and proactively manage them. Founders can better protect themselves by:

- Issuing SAFEs with a discount rather than a valuation cap, where possible, to avoid fixed dilution and retain valuation flexibility.

- Limiting the use of side letters and, when necessary, carefully restricting their scope to avoid long-term governance or economic burdens.

- Modeling dilution scenarios before issuing any SAFE—especially when multiple SAFEs are anticipated—to avoid dilution surprises at the next priced round.

- Conducting detailed cap table planning ahead of each financing round, including option pool sizing, and forecasting post-financing ownership outcomes.

Conclusion

So, are SAFEs dangerous? Not inherently—but they can be if founders do not fully understand their terms and the long-term consequences. Without careful planning, SAFEs can lead to unexpected dilution, reduced flexibility, and complex, investor-heavy cap tables—particularly when post-money caps and side letters are stacked across multiple rounds.

When used thoughtfully—with attention to structure, investor rights and cumulative dilution—SAFEs remain a founder-friendly tool for raising early-stage capital efficiently. The key is to treat every SAFE issuance like an equity deal: Negotiate terms carefully, forecast dilution realistically and always consider the impact on future rounds.